Charles Fine: The Art of Visual Perception

Front cover story ARTWEEK.LA, Vol 129, July 8, 2013. An enormous 30 year survey which fills 30,000 square feet in Ace Gallery ( October to June , 2013).

The main impression Fine’s work leaves is a cherishment of natural forms and a loving pursuit of visual detail which goes beyond outer forms – to the underlying metamorphic processes that created these natural shapes. Not only is this exhibition a moving poetic statement on environmental conservation, it is also an exploration of the art of visual perception.

Link:

http://artweek.la/blogs/art-muse

http://artweek.la/authors/lita-barrie

Text:

John Ruskin once insisted that “the first, and the last, and the closest trial question to any living creature is ‘what do you like?’ tell me what you like, and I’ll tell you what you are.” (1) The disarming directness of this question cuts through the polemics on cultural determinants and recalls, instead, the enthusiasm of children sharing their likes and dislikes on the playground. This playful expression of taste is an integral part of the process of defining ourselves through our relationship with the world around us – which even children recognize. The exertion of taste involves the affirmation of certain values and the implied or explicit exclusion of others.

Fields of Nature, Spin Cycle 1V, Table of Contents. Installation View. Courtesy: Ace Gallery Ls Angeles

Charles Fine’s magnificent ‘Thirty-Year Survey’ at Ace Gallery (October 26 through June 2013) exemplifies the significance Ruskin placed on this question of taste, because Fine had the courage to turn his back on art trends and academic orthodoxies – in an implicit rejection of artistic-academic conformity. Instead, he followed his own taste, by pursuing his lifelong curiosity about the rustic, organic, natural environs where he grew up – through careful observation of the visual nuances in Southern Californian and Mexican flora, fauna, marine fossils and simple artifacts which had fascinated him from childhood. This enormous survey, which filled all the rooms of the 30,000 square foot, museum-like Ace Gallery space, included large glass vitrines in which he artistically assembled a massive collection of lovingly preserved tiny, fragile, found objects collected over three decades, placed alongside monumental drawings, photographs, paintings and sculptures that evolved as a response to these fascinating delicate objects – which have strong resonances of places where he lived.

Seen together, the work in this exhibition has a coherence that goes beyond the individual pieces.It is an aesthetic exploration of dramatic plays on scale – resembling a zoom camera lens moving alternatively between close-up focus and a distant view. The main impression Fine’s work leaves is a cherishment of natural forms and a loving pursuit of visual detail which goes beyond outer forms – to the underlying metamorphic processes that created these natural shapes. Not only is this exhibition a moving poetic statement on environmental conservation, it is also an exploration of the art of visual perception.

In the vitrines (Table of Contents) Fine blurs the distinction between art and natural forms by meticulously assembling a vast array of tiny found objects – from washed up marine fossils, dandelions, mutant pod seeds, bone implements and antique glass bottles to ceremonial stone objects – collected from wandering Southern Californian coastal regions and rural Mexican villages. Fine has preserved these delicate found objects with shellack and casts. He has arranged them in vitrines in such a way as to call attention not only to their contents, but also to their containment – which resembles a museum collection. The containment creates an element of privacy and intimacy in sharp contrast to the monumental scale of the paintings and sculptures. Instead of merely re-hashing Marcel Duchamp’s conception of the “ready-made” (in which the gallery culturally determines what is considered art) or Joseph Cornell’s “new” tradition of the found object – Fine makes references beyond cialis online price the gallery walls to the natural environment, as the true visual origin of his art-making process.

Fieldmarks 1, Table of Contents 1, 111, 1V, 11 and Burn Cycle. Installation View. Courtesy Ace Gallery Los Angeles.

The arrangement of the exhibition reinforces Fine’s intention to give some kind of remembrance to the chance, occasional aesthetic experiences we obtain from accidental encounters with natural objects. In this way, Fine’s work suggests that art cannot be separated from the subjective experience of the viewer – that it is not something that exists objectively outside the realm of perception but something which comes into being through objects capable of engaging the close attention and imagination of the viewer. The aesthetic experience becomes primary, rather than the object which occasioned it – and Fine makes no concessions for the inattentive viewer.

This demanding work requires active engagement from the viewer as its raison d’être. Fine’s curiosity about natural forms is infectious – we see his adoration of natural objects and feel his pleasure in finding, preserving and casting his found “treasures.” He recreates this process for the viewer through the way he displays these collectibles, allowing the engaged viewer the same intimate pleasurable experience of discovering, deciphering, decoding – and finally, perceiving these “treasures” through the eyes of an artist. Fine’s work is ultimately about the art of perception, and raises tantalizing questions about the various kinds of aesthetic experience art provides by making connections to the aesthetics of natural forms. In this way, he re-examines the question of what is expected of art, its function, purpose and value in the larger context of environmentalism. The value of these “treasures” is not culturally defined – because Fine suggests that there is little distinction, or perhaps a false distinction, that conventionally separates art from artifacts and natural objects. What becomes important is the art of visual perception – more profoundly important than a narrow culturally determined perception of objects based on social and monetary values.

Visual perception is a survival mechanism. Viewed from a close-focus, or a distant focus, or from the movements of the eye down, around and across, we can make species connections and metaphoric connections with these found objects from the miniaturized view of an ecological cross-section to a macrocosmic view of the architectonics of human inhabitation and nourishment from the land.

Fine’s entree into art making came after studying briefly at Otis School of Art and Design and UCLA and taking a period alone to travel through Mexican villages – walking in the outdoor weather, observing the manner in which agrarian villagers lived in harmony with the environment, while he questioned what it meant to be an artist. During this formative period he read the American environmentalist Wallace Stegner, and major English environmentalists, including Rupert Sheldrake (who, based on his hypothesis of morphic fields and morphic resonances, conceived the universe as having its own memory) and James Lockward (who conceived the Gaia hypothesis, the interaction of organisms with their environment). These environmentalist theories provided a broader framework for Fine’s lifelong fascination with the visual information encoded in natural shapes – and Fine began to conceive of his art-works as a “living organism.” From this point onwards, his choice of subject matter and materials would leave nothing for granted, and his art-making process became an analogue to his rigorous interpretation of environmentalist ideas. Over the next three decades, he would continuously refine his techniques, developing increasingly dexterous crafting methods that allowed earthy, transformative materials to morph from one state into another – as multi-dimensional metaphors for his environmentalist view of a “living universe” as an evolving, self-regulating, continuum in which life leads to death, which in turn leads to new forms of life.

In Fine’s work the medium and technique are never gratuitous because they are always anchored in nature.Tiny sea algae pods inspire monumental cast bronze sculptures in the Alga sculptures (1989-1991); simple water irrigation systems observed in Mexican villages inspire corpuscular striated minimalist paintings in the Fieldmark series (1990-1994); small spiking tools used by Mexican villagers to plant corn inspire a large organic vertical shaped bronze sculpture Tools of Life (1987); hand-made bone implements inspire the graceful bronze sculpture Forest of Awls (1989); and parasitic plant formations inspire a mixed media sculpture on infant mortality in Under Strange Skies (1988). The earthy materials Fine selects, and his labor-intensive methods of working these materials impart a consciousness – a rustic, yet refined understated feeling of reverence for nature and harmonious human inter-actions with nature. This kind of artistic concretion – of medium and engagement with that medium – is a coalition monumentally difficult to achieve. While many artists settle for smaller ambitions – scavenging depleted media images, indulging in lame gimmicks, or attempting to shock in an effort to have their “15 minutes of fame” – in Fine’s work a patient ambition prevails.

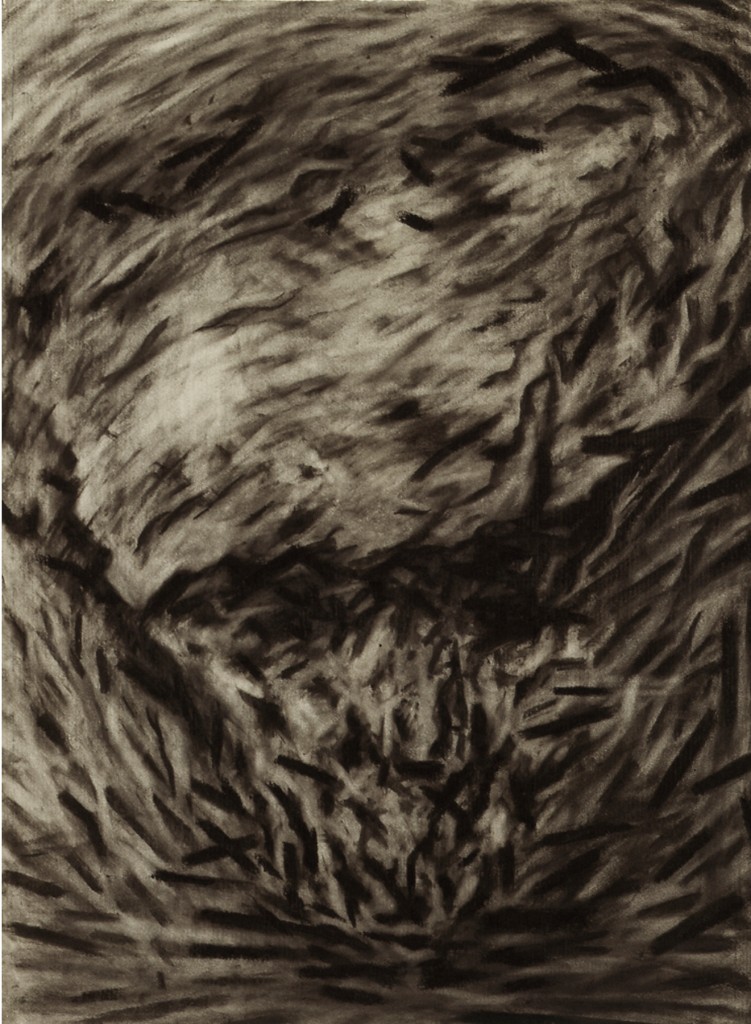

Early in his art-making, Fine introduces a human presence into the natural environment – not in a literal way, but in a subtle, suggestive way that would reveal itself through the concretion of the actual art-making process. While he was receptive to the work of Californian Light and Space and L.A Finish Fetish artists, he recalls that from the outset he wanted to “root a figurative sensibility into the landscape” in order to “re-animate it with introduced imagery.” This iconoclastic approach to making art began with a series of charcoal drawings. In one of these pivotal works,Untitled (Head 1) (1983) an evocative, face-like shape – erased and redrawn, over and again – de-materializes and re-materializes, gradually morphing into a blurry atmospheric mind-scape. Fine began to insert himself into the landscape, figuratively at first and, later, through metaphors of human labor. In another pivotal drawing from this series,The Eleventh Floor (1985), a strange fetus shape, which is both vegetable and human-like, de-materializes into a dark mental landscape.In these early drawings the artist’s body-self inhabits a dream-like atmospheric space – evoking his reflections on his place in the world and on environmental rhythms and climactic changes. Later works suggest a human presence more abstractly, through the effects of human labor and inhabitation in the environment.

Dogfish Eggcase, 1986, Oil and Alkyd Resin on Canvas 58 1/4” (H) X 31 1/4 (W). Courtesy Ace Gallery Los Angeles.

The Eggcase paintings (1986) are based on the shape of washed up sea egg cases found on Mexican beaches, which have tiny dangling arms that hook onto an ocean forest of kelp. In these ethereal, richly textured, blue-green paintings, the egg case appears like a vortex of light in an oceanic forest. The egg is a fecund object of new life and new beginnings – both fragile and resilient – gracefully floating with

delicate arms, exquisitely adapted for survival.

A series of cast bronze Alga sculptures (1989-1991) are based on tiny kelp pops, found in washed up kelp beds, each pop resembling a bead on a strand of beads – each one minutely smaller than the next bead in the strand . Fine drawn to these shapes, with their little dents, enlarges the kelp pop into cast bronze sculptures, sometimes vertical, sometimes horizontal. This dynamic play on dramatic scale variations reflects his over-arching interest in microcosmic/ macrocosmic environmental dynamics that made such a lasting impression on him from childhood visits to Big Sur.

Fine’s acute receptiveness to the visual information encoded in the natural objects he collected was driven by a rigorous interpretation of environmental aesthetics. As his aesthetic and intellectual concerns became interwoven and increasingly complex, Fine’s lifelong commitment to the art making process as a “living organism” extended into each new art work. The “living organism” kept growing by uniting and orchestrating individual pieces. The installation of the Ace Gallery survey embodies this concept of a “living organism” because it has a coherence, which is more than the sum of its parts – like a memory system which acts as a storehouse for past visual perceptions. His use of found artifacts and fragments as signifiers for archaeological discoveries and environmental mysteries implies the need to excavate beneath a cultural psyche which has become dislocated from its http://touringgreenland.com/online/ natural surroundings.

Art traditionally belonged to the private sphere between viewer and viewed. New technologies, which only offer a second-rate simulation of this inter-action that desensitizes us to the sensate experience art can offer, have invaded this private place. This represents a profound loss of the immediacy of the experience of art which moves us – physically, emotionally and intellectually engaging our close attention. As art historian Barbara Maria Stafford says, we need art that reminds us “that we are human and are incarnated on earth and we have spirit and flesh and that the two have become one.” (2)

The roots of art in hunter and gatherer and early agrarian societies came from living INSIDE nature and a feeling of oneness with nature. Industrial societies have lost this, threatened with extinction in the current era of global corporate greed and technologically irresponsible GMOs. Fine cialis online cheap turned his attention away from the art world, to agrarian societies in the rural Mexican villages he had visited from childhood and continued to visit for decades – even keeping a foundry in Mexico for making his cast sculptures – to find an antidote to the desensitizing technologies of our times.

Fieldmarks, 1993, Oil, Asphaltum, Alkyd, Resin on Canvas, 11” (H) 8 1/2 ” (W). Courtesy Ace Gallery Los Angeles.

During long walks while living in an avocado plantation near these rural Mexican villages, Fine became enthralled by aerial mountain views of irrigation systems where villagers grow corn by creating a circuitry of irrigation lines. These begin in red soil which then becomes obscured with the green growth of the corn. These first-hand observations of the constantly evolving stripping patterns in the land, created by humble people living at one with nature and weather patterns, inspired the series of Fieldmark paintings in the early 90s. These thickly encrusted paintings metamorphose from rich earth tones to lush green tones, anchored in a physical landscape which bears the imprints of human labor. Like the Californian Light and Space artists, he turns the body of the viewer into the locus for experiencing art. These visceral, corpuscular paintings incorporate the human dimensions of inhabitation and nourishment from the land.

In many of these richly layered paintings, Fine uses oil and resins with asphaltum, a tar based substance that transforms itself during the drying process This unconventional material – labor-intensive and difficult to use – changes the overlying surface as it dries, by pulling itself through overlays of oil paint – almost growing organically. The chance happenings of using this earthy, transformative material, which morphs into unexpected configurations of shapes, makes his paintings alive – in the present moment. Every inch of these polyrhythmic surfaces has been re- worked over months to allow time for the chance occurrences of inter-actions of materials cialis for sale to happen naturally – until they become so organic they appear as living structures, once again blurring the distinction between art and nature .

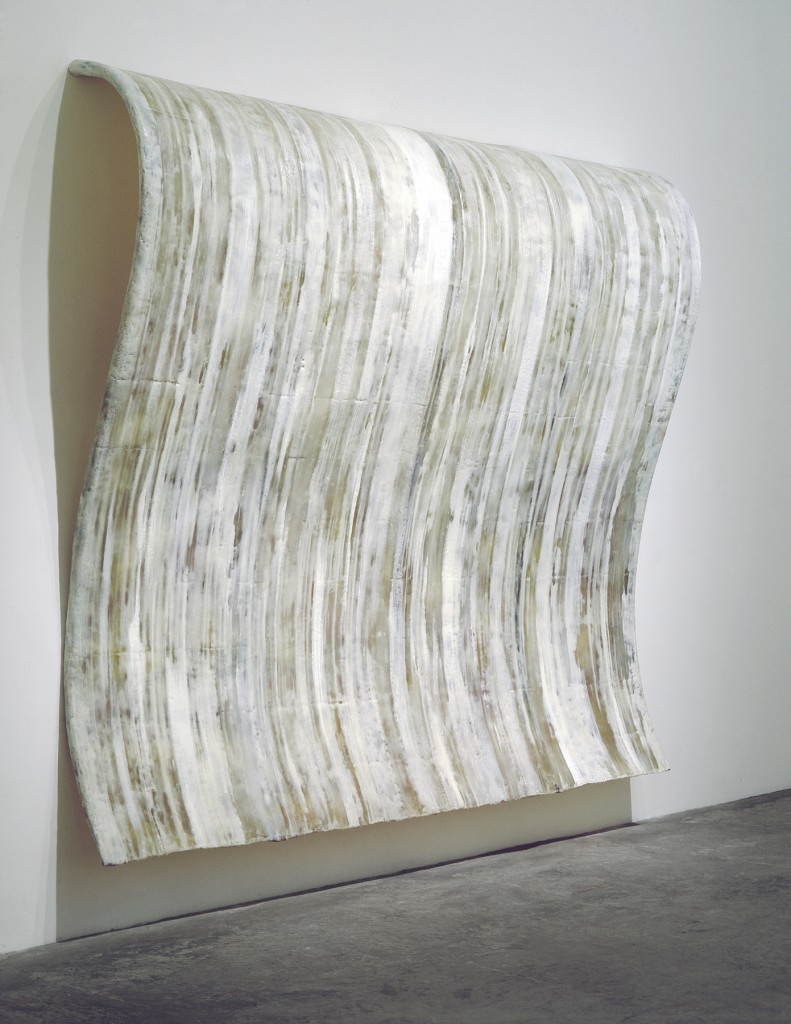

Overload, 1990, Encaustic on Steel and Resin, 84” (H) X 97 1/2 (W) X14” (D), Courtesy Ace Gallery Los Angeles.

A related series of paintings was inspired by Fine’s observation of a small viaduct that carried water down the hillside to Mexican corn fields. He bases the most majestic painting from this series, Overload (1990), on the arcing shape of the water falling into the fields after hitting a simple iron stopper. The kinesthetic quality of this encaustic work on curved steel evokes moving water – in a silent, still moment. The layered translucent surface, understated and endlessly open to interpretation, allows the viewer a contemplative space in which to imagine a shifting flow of impressions. Fine does not tell the viewer WHAT to think – only HOW to look at things with different eyes.

Under Strange Skies,1988, Mixed Media on Wood with Lead Coffin, 91” (H) X 124” (W) X 13 “ (D). Courtesy Ace Gallery Los Angeles.

Under Strange Skies (1988) demonstrates the depth of meaning that an artist – who combines the skills of an artisan, the perceptions of a poet, and the thinking of a philosopher – can achieve. In Mexico, parasitic flowers Flor de Encino, grow from the trunks of oak trees. Fine portrays these flowers strangely as wooden. In Under Strange Skies the wooden flowers stand alongside a child’s lead coffin.In rural Mexico, where infant mortality is high, infant lead coffins are a common sight in the windows of village coffin shops. The evolutionary pattern that produced the parasitic flower intrigued Fine. It reminds us of his interest in nature as an evolving living continuum – in which death creates new forms of life. But like art itself, Fine’s wooden flower embodies a fleeting moment of time held in suspense. As an artistic act of transformation the wooden flower – like Robert Rauschenberg’s eagle – is a perfect moment of the sensuous eruption of aesthetic insight.

This work, perhaps more than any other in the exhibition, typifies Fine’s ability to communicate deep feelings through meaning-filled natural sculptural materials. The power of this work lies in an aesthetic externalization which provides constraint and form to otherwise unconstrained and formless feelings.

Furnace Flowers (Group), 2010, Bronze and Stone, 45” (H) X 27” (W) X 27” (D). Courtesy Ace Gallery Los Angeles.

In a recent series, Furnace Flowers (2010), Fine refigures foundry debris of earlier bronze work into plant-like sculptures. Using the outcast debris of one sculpture to make another, embodies his environmentalist conception of his own art making process as a self-perpetuating organism.

Spin Cycle 1V, 2005, Oil and Asphaltum on canvas, 114” (H) X 96” (W). Courtesy Ace Gallery Los Angeles.

His most recent painting in the survey, Untitled Red (2012), continues from the Spin Cycle paintings he began ten years earlier. These are also inspired by the foundry. Bronze splashing on the pavement in drips, reminded him of spinning planetary systems. This painting departs from the subtle, light tonalities of the earlier paintings in this series, in the drama of the red – which suggests the sublime: a concept of infinity as boundless, formless and too great for the imagination to grasp.

Untitled Red, 2012, Oil and Asphaltum on canvas, 132” (H) X 76” (W). Courtesy Ace Gallery Los Angeles.

There has been a resurgence of interest in the concept of the sublime in analytical philosophy over the last fifteen years, with articles appearing in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism and The British Journal of Aesthetics, publications by Malcolm Budd, James Kirwan, Kirk Pillow and most importantly the late French philosopher, Jean Francois Lyotard – who first introduced the postmodern sublime into theoretical discourse in the 80s and continued to theorize its implications for contemporary painting until his death (in 1998). As Lyotard argued, “ The spirit of the times is surely not that of the merely pleasant: its mission remains that of the immanent sublime, that of alluding to the non-demonstrable.” (3) This marks a paradigm shift as contemporary philosophers draw from the ancients and Immanuel Kant (the seminal philosopher on beauty and the sublime, whose significance is now being re-evaluated) to find a new cultural theory for the 21st-century. Fine’s rigorously intellectual art work, parallels this philosophical shift of interest in the postmodern sublime – although that was not his conscious intention. By turning his back on frivolous art trends, he moves ahead of them.

The late, Robert Hughes conceives “the basic project of art ” to “make the world whole and comprehensible…not through argument but through feeling,” and in this way, “to pass from feeling to meaning.” Hughes insists that this can only be achieved by artists with the “direct sensuous and complex relationship with the world around them” that children have. This, Hughes suggested, is “the lost paradise art wants to give back to us.” (4)

In an era when such ideals have been abandoned by a trend-obsessed art world which often prefers sensationalism to sensitivity, the abject to the beautiful, the simulated to the sublime, Fine’s complex, contemplative work is an act of quiet artistic and intellectual dissidence. Fine clearly understands that art’s power resides in quiet reflection (recalling Susan Sontag’s notion of the “Aesthetics of Silence”) rather than its ability to shock and scandalize – which, after all, the Kardashians can do louder and more lucratively, than avant-garde artists. Perhaps, the avant-garde has finally exhausted itself as we enter the new technological age.Today we need a more quiet art which can transgress the norms of the noisy ambient culture of desensitizing, numbing, rapid moving banal imagery – by anchoring itself in something which is NOT degraded, debased, and simulated. Fine’s work is a powerful wordless statement on environmentalism, free of polemic, using the language all classical artists use: medium and technique, “the nuts and bolts” of all serious art making.

Vision is our primary sense.The retina is part of the brain, a kind of mini-brain. Yet we often forget how we collect and store visual information.The fovea, is the central specialized region of the retina directed to objects of interest and the recognition of patterns – which Colin Blakemore suggests we might call “the seat of the self.” (5) Fine’s work opens our eyes to the natural world we inhabit, directing our foveal vision to detailed visual nuances – an exercise in visual intelligence.

Ruskin argued that “Taste is the only morality.” (6) Fine’s work has a gravitas, precisely because he had the integrity to remain true to the natural things he “liked” from childhood – an exertion of taste which defines our place in the world.

References

1 Ruskin, John. “Traffic.” The Crown of Wild Olive and the Cestus of Aglaia. Ed. Ernst Rys. London: J.M Dent and Sons. 1915.

2 Stafford, Barbara Maria “Interview” by Suzanne Ramljak, Sculpture. May/June 1994.

3 Lyotard, Jean Francois “Presenting the Unpresentable:The Sublime” Contextualizing Aesthetics From Plato to Lyotard. Ed. H.Gene Blocker & Jennifer M. Jeffers. Canada: Wadsworth Publishing Company. 1999.

4 Hughes, Robert “The Mechanical Paradise” Episode One. The Shock of the New, BBC. 1980.

5 Blakemore, Colin “The Baffled Brain” Illusion in Nature and Art Ed. R.L Gregory & E.H Gombrich. London: Duckworth, 1973.

6 Ruskin. Op.cit.

Note

Special thanks to Charles Fine, for the in-depth discussions of his work, which helped to inform many ideas expressed in this essay.

Note

Published in Artweek.la July 8, Vol 129

http://artweek.la/authors/lita-barrie

http//artweek.la/blogs/art-muse